attempts, we dropped it astern and tied with a long bowline to a substantial looking dolphin near the old float.

A small seal watched the entire anchoring process. Later, while dinghying around the nook, he (she?)

dove off the old float and surfaced six feet behind us. He stared at us for perhaps ten seconds

submerged briefly (but totally in view through the clear water) and then resurfaced. Apparently

deciding that we were neither interesting nor threatening, he swam a hundred feet away and continued

to shadow us during the hour or so we rowed around the area. It was obvious that this was his cove.

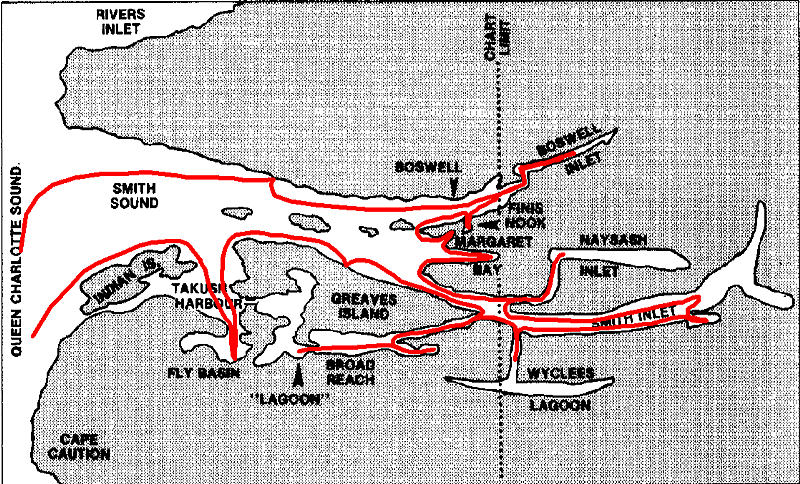

Leaving Finis Nook, if you continue west in Boswell inlet for a mile, swing south around Olive

Point and head east again, you'll enter the middle of Smith Sound's three fingers, in which are

located Ethel Cove and Margaret Bay. This area is shown in detail on chart 3797. (Finis Nook also

shows better detail on the Margaret Bay chart.)

Ethel Cove has depths suitable for anchoring, but appears open to a prevailing westerly swell.

Margaret Bay, a few hundred yards south, is a mile long and is protected from the swell by Chamber

Island about half way in. Only a wharf in ruins remained at the location of an abandoned store,

oil tanks and post office. During our visit, a deer browsed in a flat area we

|

|

presumed to be the townsite. The bay is quite narrow and shallows quickly near the wharf, but adept

anchoring and/or stern-tying techniques would provide a great base camp for exploring the townsite

and the mudflats to the east. If that area were judged too tight, the east side of Chambers Island

also offers protection, but would still require stern tying.

When leaving Margaret Bay, favor its north shore to avoid Camosun Rock. Rounding Ripon Point puts

you in Smith Inlet, the southernmost finger. About six miles into the inlet, uncharted Naysash Inlet

branches northeast. We ventured about a mile east to Hickey Cove, where the inlet turns north. This

pretty place offers secure anchorage. North of here about a mile and a half, the inlet turns east

again for a reported six more miles, but it narrows and shallows quickly, making it unsuitable for

exploring except by dinghy.

Reentering Smith Inlet, it is possible to cruise east (off the chart) several miles further;

the inlet continues about 12 miles. We traversed half of it and saw no obvious dangers. On the

south shore, still in the uncharted portion of Smith Inlet, Wyclees Lagoon branches south three

miles, then tees east and west for about six miles each direction. The lagoon is not shown on

chart 3776, but is shown in white (unsurveyed) at the top of chart 3552-Seymour Inlet

and Belize Inlet. Again,

|

|

the narrowness and assumed shallowness of the entrance overwhelmed our desire to explore the lagoon,

and we did not enter.

Back on the chart, due south of Naysash Inlet, is Ahclakerho Channel, which runs southwest

for five miles between Greaves Island on the north and the mainland on the south, leading to

Broad Reach. The Coast Pilot describes it as tortuous. The large volume of water in Broad Reach

in relation to the narrowness of Ahclakerho Channel makes for strong tidal currents in the channel.

The entrance to Broad Reach at the southwest end of the channel is not as straightforward as the

chart indicates. It is here that the events noted in the opening paragraph occurred.

We felt confident that we had observed the channel carefully, and knew where we were.

But this was one of those times when things look differently from the helm of your boat than

they did on a chart while seated in your favorite chair. Thus we found ourselves being propelled

toward the wrong end of the island, while the channel at the right end looked like nothing more than a bight.

Saying a silent prayer to the guys who make Canadian charts, I pushed the throttles forward

and cranked the wheel to the right. We crabbed in the current, the bow pointing toward the fallen

snags jutting out from the north shoreline. As we passed the eastern

|

|